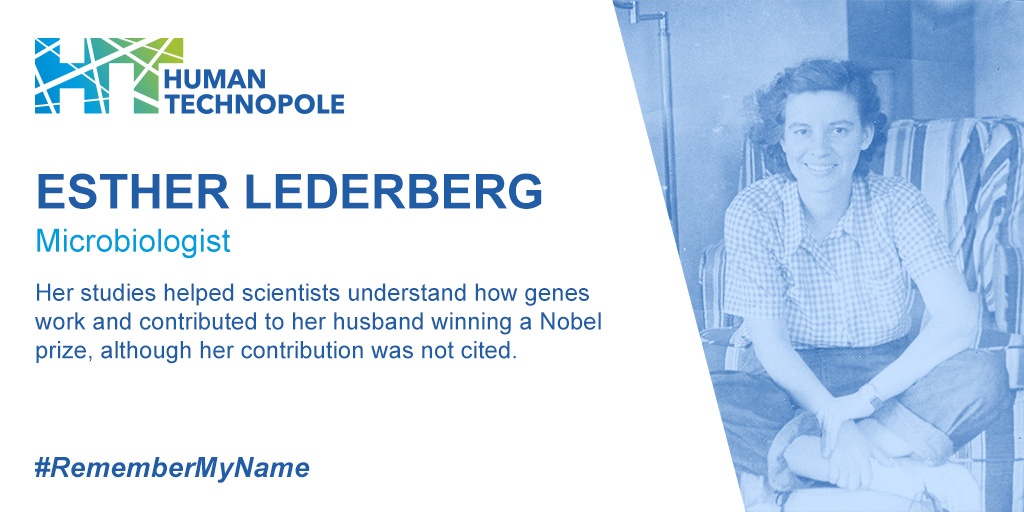

Esther Lederberg

Microbiologist

Born in 1922, Esther Miriam Zimmer came of age in New York City during World War II. Her family was poor. Her father worked as a printer, his siblings as garment workers. But Esther, a voracious learner, would fly far beyond the Bronx neighborhood where she grew up. At Hunter College, which she attended on a scholarship, she studied biochemistry, even though she was told the subject was “too difficult for women,” Simon says. She went on to earn a master’s in genetics at Stanford University, where, as Simon writes on the website, she sometimes made ends meet by eating frogs’ legs after dissections.

Esther met Joshua Lederberg shortly before she graduated from Stanford. They married months later, when she was 23 and he was 21, and soon headed off to the University of Wisconsin, where they would begin years of fruitful collaboration and she would earn a Ph.D. Joshua, by all accounts a brilliant thinker, became famous for his big ideas. Esther, meanwhile, developed expertise as an experimentalist, doing the often tedious work of testing big ideas in the lab.

“I’m sure that Esther benefited by being in Josh’s presence,” says Millard Susman, a professor emeritus of genetics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who arrived shortly after the Lederbergs left. “But obviously Josh benefited by being in Esther’s presence too.” Throughout the 1950s, they published papers together and apart as both made discoveries about bacteria, proving that those simple species could reveal “the chemical events that all life depends on,” as Susman puts it.

Joshua won the Nobel Prize for upending the notion that bacteria always make identical copies of themselves when they reproduce; he discovered that they can also engage in something that looks more like sex, mixing genetic material and producing something new. Esther worked alongside him and made related discoveries, like identifying a “fertility factor” that allows that mixing to happen. She also discovered a virus she named lambda phage, which would later help reveal the mysteries of DNA and the expression of genes. Such revelations, which the Lederbergs worked on with other collaborators as well, unearthed basic principles of what would become molecular biology, setting the stage for fields like genetic engineering.

The Lederbergs took joint credit for developing a technique called replica plating. For decades, scientists used a toothpick-like tool to move one cluster of bacteria at a time in the lab. In 1952, the Lederbergs showed that hundreds of colonies could be moved at once by using a material like velvet. They used replica plating to do landmark work showing that mutations happen randomly in evolution rather than because they are needed—a hotly contested topic at the time—and the process was adopted widely. “It’s the difference between handwritten manuscripts and a printing press,” says Ferrell, a professor of biology at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Ferrell sees Esther “all over it.” After all, she was a practical scientist who came from a family of textile workers.

The question of who gets credit in a laboratory is always a messy business, but there is little doubt that Esther became marginalized after her husband won the Nobel Prize. In 1956, two years before, the Lederbergs had jointly won the Pasteur Award, a prize for “outstanding contributions” to science. Joshua had won another award, the Eli Lilly, in 1953 and subsequently told a reporter, “Esther should have been in on that too.” In a remembrance written after Esther died, noted microbiologist and Stanford professor Stanley Falkow said Esther’s “independent seminal contributions in Joshua’s laboratory … surely led, in part, to his Nobel Prize.”

Joshua did recognize her in his Nobel lecture, saying he had “enjoyed the companionship of many colleagues, above all my wife.” But it was brief, and after they got home, he was invited to lead the department of genetics at Stanford while she was offered a research-associate position in a different department. The era of their being “a husband and wife science team,” as one 1956 article put it, was ending.

Only the two of them could say why their relationship faltered, but by 1966 they were divorced. One young scientist Esther befriended in the 1970s, Dennis Kopecko, recalls her being generous and uncompetitive but also “irascible” in the years that followed. Joshua, he says, became a “giant in the field” and would walk by Esther and Kopecko in the Stanford cafeteria without acknowledging their presence.

According to Simon, Esther eventually received a faculty appointment only because she was willing to accept a job without tenure. Another colleague, Brandeis University historian of science Pnina G. Abir-Am, says Esther had to fight to keep a job at the school after she and Joshua split up. Though she worked at Stanford until retiring in 1985, “she never had a position commensurate with her position in science,” Abir-Am says. (Stanford, reached by TIME, did not provide comment.)

Mark Martin, who developed a friendship with Esther while he was a graduate student at Stanford in the 1980s, is one of many scientists who laments that Esther’s name has been absent from textbooks. Now an associate professor of biology at the University of Puget Sound, Martin teaches students about her when he explains bacterial genetics. “I don’t think that you own something that you discover. It was there before you were born,” he says. “But I do believe in credit. And that means that if somebody does something, you bring that up. That’s your job.”